Hope is not an easy thing. It is not simple. It is fierce, valiant, bladed. Hope is not the thing with feathers but the thing with teeth. It is hard-won and hard-kept, a candle sheltered in a storm at the expense of burned hands.

The trouble with hope, or at least the trouble with the general perception of hope, is that its complex nature is only understood once one has been hopeless, once one has struggled and fought through the tempest to seize it and wield it as a sword. To know hope in truth is to first know despair.

This is why hope is often known only from the outside. It is seen as bright eyes and quick smiles and easy laughs, as a can-do attitude, as optimism. The determination behind it all, the white-knuckled grip on the single thing which keeps the hopeful from plummeting into the endless wailing nothingness always there and ready to swallow them whole, goes unnoticed.

This is why people look down on Snow White and other fairy tale heroines of her nature.

Snow is often accused of being passive, useless, pathetic. She waits around for a prince to save her, say her critics, instead of saving herself. She should have fought.

They never seem to realize she did fight. She fought hard, and had she done anything less she would likely have perished long before the apple passed her lips.

You know the story well enough, even if you only know the Disney version. I give Disney plenty of grief, and the company has always had a tendency to soften and simplify fairy tales, but at least when it comes to the older films, they tended to put real effort into getting the story right (at least on a structural/archetypal level). Despite changing Grimm’s ending, tossing the Queen off a cliff so she could perish offscreen instead of forcing her to dance at Snow’s wedding in a pair of red-hot iron shoes until she fell down dead, Disney’s version is more or less true to the original. Still, to understand Snow White, it’s worth going over her tale.

Snow White grows up with tragedy. Her mother dies shortly after her birth, and that loss alone would be terrible enough. Of course, it doesn’t end there. Her father remarries, and poorly. In Disney’s version, her stepmother, the Queen, forces her into servitude. This is not the case in Grimm’s, but either way the Queen is no mother to Snow White. That, too, would be more than enough to scar a young girl for life.

In Grimm’s, the Queen only truly begins to hate Snow when she reaches the age of seven. This is when the mirror declares her fairer than the Queen. The girl is seven years old, and the only mother she’s ever known, however badly the woman fits that role, hates her more than anything.

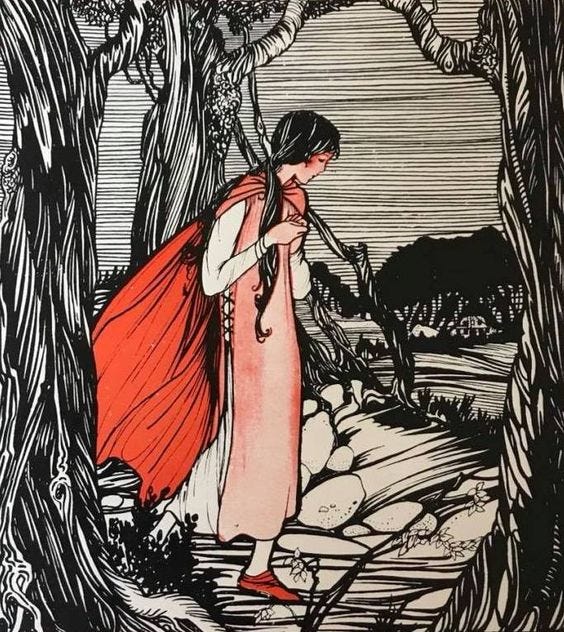

Through it all, Snow White remains hopeful, remains kind. The loss and abuse she suffers are never enough to make her bitter and despairing. No, she doesn’t fight back against the Queen, not in the way we usually think of fighting. What would be the point? What child can fight a Queen? There is no point in running away, no better place to go, no rebellion to ignite. She is young and small and delicate, and all she can do is endure. Were you in her position, do you think you could have done more?

Years pass. Snow’s beauty grows, as does the Queen’s hatred, and in time she grows so beautiful she has to die for it. (It’s an old crime, beauty. Psyche committed it against Aphrodite and she, too, was sentenced to death.)

The Queen summons her Huntsman and bids him kill the girl and bring back her heart. He brings Snow to the forest fully intending to do as he was told, but the princess begs him to spare her life. He relents because of her youth and beauty, but fairy tales being what they are, I think there’s a little more to it than that. I think he does it because she embodies youth and beauty, along with their deeper implications. And I don’t believe she could have done that were she not strong enough to hold onto hope all her life.

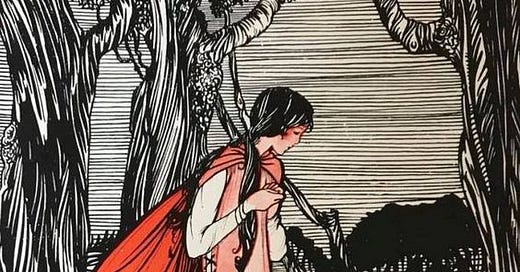

Into the forest she goes (and into the forest they always go). The Huntsman kills a young boar (or a young fawn, depending on the version) and brings its heart to the Queen, who salts and cooks and eats it.

People always seem to forget about that part of the story. The story itself seems to forget about it, as the Queen never bothers with the heart once she’s killed the girl. I’ve never understood how. As far as I’m concerned, it’s the heart of the tale (pun intended). It is not simply that the Queen hates Snow White, not simply that she wants her dead. She wants to devour her. Destruction is not enough; she must consume.

Snow White panics in the forest. This is another thing for which she is criticized, despite the fact she is a sheltered child who barely escaped death a moment ago whose only recourse is an endless expanse of trees filled with predators as hungry as her stepmother.

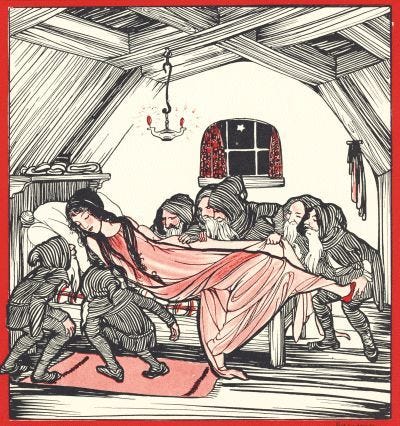

Next come the dwarves, whom she wins over through not only her outward youth and beauty but her kindness and industriousness.

And finally, there is the apple. This, I think, is what Snow is most severely criticized for. Shouldn’t she have known better? Shouldn’t she have done as she was told and not opened the door for anyone? Shouldn’t she have recognized there was something strange here, something wrong?

Well, yes. But there’s more to it than that.

I’ve been talking about Snow’s virtues, her gentle nature and abounding kindness and unshakeable hope. That doesn’t make her perfect.

Snow White is a young girl, and despite the unfortunate circumstances of her life she remains naïve. Combine this with her optimism, with her enduring belief in the goodness of humanity, and her virtues become a weakness. Can she be blamed for that, really, the consequence of her nature? (And perhaps there is still more to it. Perhaps she saw the old woman selling her wares and felt again that ache for a mother, and couldn’t bear not to trust her.)

So. The apple. The death. The kiss. Here again we reach one of the great criticisms of our time, and only our time, for only our time is capable of this oblivious absurdity. The kiss, argue the critics, is creepy, and it’s not feminist.

To the latter point: Well, duh. It’s a centuries-old fairy tale. It doesn’t care about your modern sensibilities. And there is, in fact, more to life and more to storytelling than conforming to any political ideology.

To the former: Oh, for heaven’s sake, would you think critically for five seconds? No, this isn’t about some necrophiliac coming upon a dead girl and laying one on her. No, this isn’t about kissing a girl without her consent. We’re talking about a fairy tale here, and fairy tales are so redolent with symbols they’re almost more meaning than story. (This, obviously, presents a serious problem for modern analysis.)

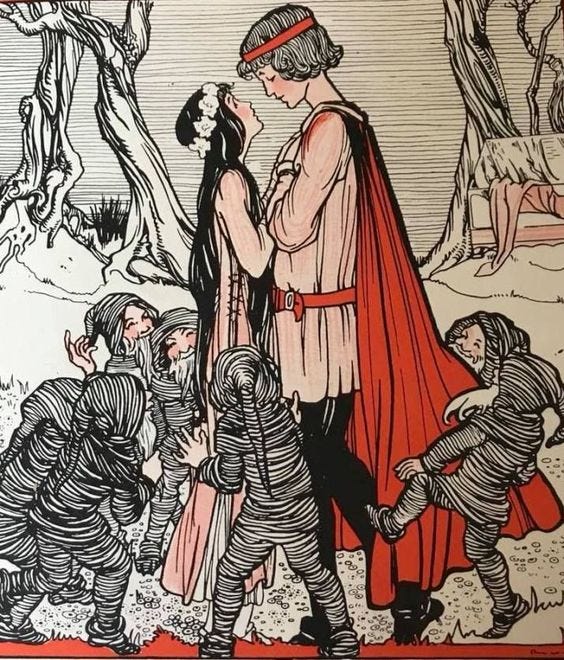

The kiss is not merely a kiss, nor is the Prince merely a prince. The kiss is symbolic of Snow White’s sexual awakening. The Prince is symbolic of her animus, her aggression and masculinity. When the Prince kisses Snow White and brings her back to life, she incorporates those darker, more mature parts of herself into her being. She dies a girl and wakes a woman.

Snow White at the end of the tale is a far different person from Snow White at the beginning. We don’t get to see this in the story, but we can extrapolate from the symbols and archetypes given. The woman who rises from the glass coffin is no longer a naïve girl, no longer one to panic in the forest or take a gift from a witch. She knows the forest, knows the witch. She is wiser, stronger. Soon enough she herself will be a queen.

Snow White does not simply wait around for a prince to save her, even in the Disney version. Yes, Disney’s Snow White longs for a prince. That’s not a bad thing, to want love, to recognize there is a part of oneself unreached and unexplored and to wish otherwise. It’s also not a bad thing to want help, or to seek it (and it can be quite foolish not to). But wanting a prince and waiting for one are two different things.

Snow White may yearn for her prince, but she makes do without one. As a child she learns to make the best of a terrible situation, to endure abuse and to love without being loved. When her life is threatened, she does all she can to preserve it. She pleads with the Huntsman and braves the forest. When she finds the dwarves, she does not expect to be treated as a princess. She keeps their house and brings new joy to their lives.

When the witch comes, her strengths become weaknesses, and she dies. And the Prince saves her. But on a deeper level, she saves herself. She has been saving herself all her life.

Snow White’s strength is a soft one, a quiet one, and too often it goes unnoticed. Her strength is kindness in the face of cruelty, hope in the face of despair. She earns her happily-ever-after, fights for it with all she has, and even now the world sees her smile and never realizes she’s baring her teeth.

We, the living, die. We die when childhood falls away, emerging as from a cocoon, unrecognizable to ourselves. In questioning, one finds passions and purpose realigned. Many years later, we die once again and are reborn beyond passion, beyond purpose, through the trials behind us that cut away detritus, sift impurities, and refine the gleaming substance beneath. Once more, walking the lengths and breadth of this world, we die and transform. Bathed in the white of wisdom, we settle and enjoy the fruits of our life's labors until the final time we lie down and rise no more.

Yet even that is not the last resurrection, merely transcendence. What lies beyond the veil of Life, no one knows though all will learn in time. It is not the proud, the loud, or even the winsome that embrace the many little deaths that living endures; but the silent warrior who lifts their chin at darkfall and yearns to know what comes after.