Shannon Hale’s The Goose Girl is not the sort of retelling that has become so popular in recent years. It is not a “twisted take” on the original. It is no darker than Grimm’s version, or at least not notably so. It does not place the story in a revolutionary location, put a weapon in the heroine’s hand, or titillate the reader. It is, simply and beautifully, The Brothers Grimm’s The Goose Girl, only with flesh on the bones.

Fairy tales are skeleton stories, you see. They are old, so old that all that’s left of them is what one teller remembered from the one who told them, who told them, who told them, and on and on it goes. All that’s left of fairy tales are the basic structures, the archetypes, and the symbols. Fairy tales are all teeth and bones and grave goods.

A retelling, then, is a sort of archaeology, and more so a sort of necromancy. It is opening the tomb, peering about, holding strange artifacts up to the light and guessing at their purpose. It is pushing away the heavy stone lid of the sarcophagus to say the words that will give back to those dry bones organs and muscle and flesh and breath.

Of course, they never come back quite the same.

It’s a peculiar kind of resurrection, an imperfect one. You can’t restore who they were. Not exactly. What you bring back is a version of who they used to be that is shaped by your perception of what now lies in the tomb.

Fairy tales change in retellings the same way they’ve always changed in the journey from one tongue to the next. The teller finds some things more important than others, asks questions and arrives at answers others will not. That’s at least half of a retelling: answering questions.

Take Gail Carson Levine’s Ella Enchanted, a Cinderella retelling with which I spent literal years of my life completely obsessed. The original tale tends to raise two main questions. One, why doesn’t Cinderella fight back? (The real answer to that one, of course, is because she was an abused child with nowhere else to go, and so chose to do what she could to make the best of a terrible situation.) Two, why does the fairy godmother wait so long to help? Levine gives satisfying answers to both of these questions. Ella doesn’t fight back because she’s cursed with obedience. Her fairy godmother doesn’t help until the ball because big magic (like enchanting a child to be obedient) is risky, and in fact it’s not Ella’s godmother who helps her but a different fairy with questionable judgment.

Some retellings are based more in raising new questions than satisfying the old. (If you read Bruises, my retelling of The Princess and the Pea, you probably realized the question I asked was, “What sort of monster purposefully seeks out a woman so easily hurt?”) Many of these stray far enough from the original that they become entirely new stories with only the trappings of the old. These highly speculative retellings have grown more popular in recent years.

(And if you’ve ever found yourself wondering what Vasilisa the Beautiful would be like if you set it in modern Brooklyn, made Baba Yaga’s house into a convenience store, and went all-in on that death-metal-on-acid feeling you get from Russian fairy tales, do check out Vassa in the Night by Sarah Porter.)

The Goose Girl belongs to the former category. It is made to answer the questions raised in studying the bones of the fairy tale. As I don’t believe it to be a particularly well-known story, let’s take a look at the bones before we address the questions:

A princess is sent by her mother to another kingdom to be wed to the prince of that land. She is accompanied by her lady-in-waiting and her talking horse, Falada. Her mother gives her a cloth stained with three drops of her own blood as protection.

In the forest they travel through on their way to the kingdom, the lady-in-waiting becomes rebellious. When the princess asks her to fill her golden cup with water from the nearby stream, the lady-in-waiting refuses and the princess is forced to lie down to drink from the stream without a cup. She is comforted by her mother’s blood.

On one of these occasions, the princess loses the bloodstained cloth in the stream.

The lady-in-waiting steals the princess’ identity.

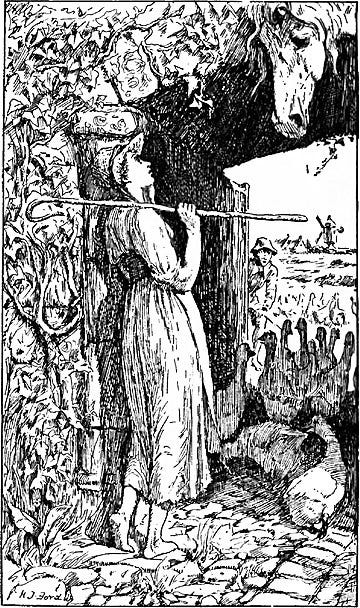

In her betrothed’s kingdom, the princess is assigned to tend the king’s geese with the goose boy, called Curdken or Conrad.

The lady-in-waiting has Falada killed. His head is stuffed and placed at the top of an arch beneath which the princess walks every day. The princess converses with Falada’s head whenever she passes by. Horse girls everywhere cry, deeply betrayed by where this talking horse plot point went.

The goose boy tries to steal some of the princess’ beautiful blonde hair while she combs it. She calls on the wind to blow his hat away and keep him distracted until she has her hair braided in a crown.

The goose boy tells the king about the witchy weirdness of his coworker.

The king overhears the true story when the princess believes herself to be alone.

Framing the story so the lady-in-waiting doesn’t realize he’s talking about her, he asks her what the punishment for her actions should be. She says a person who has committed such unforgivable crimes should be stripped naked, stuffed in a barrel lined with nails, and rolled through the streets.

All is revealed, the prince and princess are married, and they all live happily ever after. Except the lady-in-waiting, who is very dead, having been given the punishment she named.

You can see why Disney never tried adapting this one.

Cowards.

Anyhow, we were getting to the questions. Which are, mainly:

Why can Falada speak?

Why (the hell) can the drops of blood speak?

What sort of person would name their child Curdken?

Why on God’s green earth can Falada’s decapitated head speak?

Why can the princess speak to the wind? And why the hell hasn’t she put that particular talent to use before, perhaps for more important things like blowing her traitorous lady-in-waiting off a cliff?

Why (and I say this as a devoted defender of fairy tale heroines, a horribly misunderstood group) is the princess so damn pathetic?

You did ask that one about Curdken, right? So did Shannon Hale, apparently, because she went with Conrad, and thank goodness for that.

Hale answered every one of those questions. Falada can talk and the princess can speak to the wind because everything in the world has a language that can be learned, and some people (like the princess) are born with the first word of a language on their tongue. The languages all work differently; for instance, when a horse is born it says its name, and if you hear the name and speak it you create a telepathic bond between yourself and the horse.

The blood can’t speak, the princess merely takes comfort in it, because its speech in the tale didn’t add all that much to the plot and also it was just plain weird. Falada’s decapitated head also loses the power of speech in this retelling. He merely becomes a conduit for the wind’s speech. The princess learns the wind’s tongue over time, which is why she does not and cannot use it earlier in the story.

And Ani (or Isi), Hale’s version of the princess, is not pathetic. In Grimm’s version, the princess being “meek” is framed in a negative light, but she never grows past her meekness (unless you count her marriage to the prince and her symbolic assimilation of her masculine side). Ani begins her story much like the original princess—anxious, unsure of herself, and uncomfortable with conflict—but she’s got a backbone from the start.

Ani is exactly what a fairy tale princess should be. She is kind, clever, and brave. She wins friends and allies through her gentleness and creativity, telling tales to the rest of the animal workers by the fire. She uses her influence to fight back against the brutality and injustices of a kingdom that she makes her own—not with a sword but a sharp tongue and deeply-held values.

The king is not her savior in this version. He doesn’t trick her into confessing her story to an iron stove, as if Ani would ever fall for such a trick. Ani takes control of her story, her fight. She has help, and plenty of it, but it’s help she earned. Much like her happily-ever-after, which takes a more bittersweet tone than the old story.

Shannon Hale brought out from the tomb of The Goose Girl a story of struggle, courage, and kindness. They were beautiful bones, and I love them as such, but I hope you’ll forgive me for loving them yet more when they’ve been given a beating heart.

If you haven't read The Goose Girl, go read it. If you have read it, do yourself a favor and reread it.